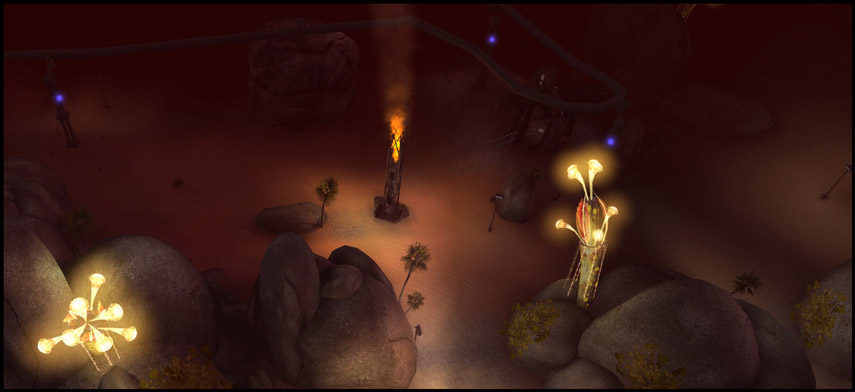

With almost two decades of experience in CG and the video game industry, Rogelio Olguin has garnered a wide variety of knowledge and skills. Olguin has worked at Framestore NYC as a commercial 3D Artist, and at 4mm Games LLC in NYC on DefJam Rapstar. He went on to work on triple A titles including Tomb Raider by Crystal Dynamics and The Last of US and Uncharted titles by Naughty dog. Rogelio attended the School of Visual Arts in NYC and from that produced the best short of the year, "Abyssus," voted by NYC CG industry judges. But before beginning his studies in New York, Olguin worked on Unreal Tournament 2004 as a contract level designer, utilizing his already established experience creating levels and environment for games that he started as a young teenager. Olguin went on to become an instructor for The Gnomon Workshop and created the course, Substance Designer Texture Creation. He has also done many Workshops and publications around the world that include companies like Allegorithmic, Amazon Games, and The Mill VFX.

GW: What do the daily demands for an environment artist look like?

RA: At work, what I mostly do day-to-day is modeling and texturing. Though, realistically, the main aspect is really communicating and talking with team members throughout the day and having critiques and planning sessions. The day-to-day changes a lot and it is this flexibility that really makes me love environment art so much. I get to interact with many people at work from all kinds of disciplines. The environment artist position has almost become an intersecting point in production where all the elements of the game tie in. One day, I may be planning with the designers, and on another day, I’m with the VFX team to get an element of the environment done. So, as an environment artist we do not have many typical days and it involves a lot of active team work. On the days that are not so busy or active, I am generally modeling, texturing, or sculpting.

GW: Before your professional career began, was there a personal project from your past that still stands out to you today as pivotal or influential? Which one, and why?

RA: I remember when I decided to make my first single player story for Duke Nukem 3D as a modder. I ended up making a whole single player campaign that was the same length of gameplay as the actual game. Funny enough I should have known better and actually sent it to 3D Realms or tried to pitch it to someone because it was a complete game with some new assets. I still have it in my old Zip drives somewhere. It was the first time I realized how much I had really learned. While I did construct levels for games prior to Duke Nukem 3D on games likes Doom and others, Duke was perhaps the first one that I took that far. At that point, it was still just something fun to do while I did not have homework from middle school. After that, I took it further and felt like it was more than a hobby and moved to games like Quake and later the Unreal universe games. I loved how simple the games were back then when I could do everything from scripting, design, modeling, texturing, sound, lighting, and storytelling. For a young teen to have that much power, I went from being a pretty adventurous outdoor kid, to a kid that was obsessed with computer games and creating content for them.

GW: You’ve worked both in traditional painting and traditional sculpting and, of course, digital art. How do you view the two platforms (traditional and digital) and how did you translate benefits or challenges from both or either?

RA: I love art and making it. I wish I had more time to paint and sculpt traditionally, when I do have the chance it is a complete joy. When working on traditional vs digital I am more conscious about things like my heart rate as deep concentration is something that can be harder with digital, especially in an environment like a game studio. I have found that changing from different techniques or mediums has helped me immensely in understanding concepts that are hard to grasp if you concentrate too much on one area. Early on, many of my instructors would tell me to concentrate on a specific skill or profession, and I think this is a sure-fire way of getting tired of art or the craft in general. In my free time, I try to do projects that are vastly different than what I do at work because firstly I have already reached a commercial accepted level of quality on that end so what is the point of practicing on something that I do all the time, and that I do well. Instead, I practice on what I am not as good at, for example characters or traditional mediums because it brings different challenges that keep me learning as an artist. Also, traditional art helps me with direct confidence. If I make a brush stroke on canvas, then I better make a good one; because I do not have the luxury of undoing the stroke. So, traditional in many ways has also made me have a speed boost and not doubt what I do digitally as much. I have gotten comments about my speed from co-workers or people who have seen me work many times and I attribute a lot of it to practice, but also not doubting myself as much anymore and letting art flow vs fighting every second of it. In conclusion, changing mediums, styles, and programs have helped me in many ways.

GW: Having an acute understanding of several departments in the production pipeline, such as Level Design, Lighting, UI, and Environment Modeling, and Environment Texturing is one of your key strengths. How did you achieve that level of experience-depth throughout?

RA: Part of it is just life events. As I mentioned prior when I was just doing this for fun as a modder it was just a journey of learning. If I need to script or code something I learned enough to do that one task, If I wanted to design a layout I looked at what was done in the game, and also just simply played that layout over and over until it was fun. As games became more complex, lighting got introduced and I had to learn that aspect. It all happened naturally and organically through just having fun in the space of modding these games. In my first game career job, I was a level designer which meant also world builder at the time. I learned so much by working with amazing developers like Cliff Bleszinski and people at Epic Games. While I love art, another passion I have is for games, and not just the art side, but everything about them. To this day, I can say I am still fascinated with the whole creation process of games. While it has significantly become more complex to make a full game, the tools are in a new renaissance that the complexity of reaching high quality assets is becoming much simpler in the right hands. I am still coming up with ideas for games of my own, and while none of them have become anything as of yet... I am currently in the process of something in my free time that maybe could.

GW: You have taught at The Gnomon Workshop sharing with audiences the intricacies of your work. Is there an experience that stands out to you about Gnomon that you can share?

RA: Thanks for having me over, it has been a blast! I do remember several moments that left me floored in many ways. The one that left me almost speechless happened when I was in Substance Days with the Allegorithmic team, in which an artist come up to me to shake my hand while saying that the tutorial I created for Substance Designer Gnomon DVDs gave him his first industry job. He explained that the tutorial is one he practiced many times over and created a whole texture portfolio to be able to enter his first job. The other time was not when I was presenting, but when my spouse, Sharlene Lin, did her own presentation for Substance Day’s a year later and I was able to see her presenting to everyone, and seeing the attention people had on the subject she gave. These are the moments I want to have with the art community, and hope, in some way, to give something back, too. The art game community can be daunting. The talks Gnomon curates are a great forum to connect with various artists. I have been in the audience many times at Gnomon talks, and enjoyed the space to learn with student and professionals alike.

GW: Substance Designer has so many pros. Are there any cons that you have found? If so, how do you mitigate those and find solutions?

RA: This is going to sound like I get paid by Allegorithmic for sponsoring this product, but I assure you I am not. I honestly do not see any real cons. All the cons can be alleviated through creating tools within Designer to make my life easier. Sure, out of the box the program is pretty bare bones; but once you really go deeper into this program you will notice it is limitless, and honestly I am still learning and improving my workflows to this day. This is a tool that keeps on giving. When it comes to texturing and workflow solutions this tool cannot compare with anything in the market. Also, if you tie this with Painter, you have two unbeatable packages that have changed gamedev on the art side forever. The only limit might be a super technical aspect that most likely is not even limiting when it comes to general production needs. Now, the tool is not perfect, and has quirks, but the Allegorithmic team does a good job to find and squash them. I remember when it was first introduced to us at Naughty Dog and since then where it has gone. The Allegorithmic team worked very close with us at ND to improve workflows for the artists, and I am proud to say that the artists at work improved the core Designer tool as a whole. Jokingly I say that everyone in the industry is using our tool because we helped influence some aspects for sure. But, generally, Allegorithmic have been a great team to work with, and I personally count them as part of our team and also as close friends.

GW: What has been one of the highlights to working on big games like Tomb Raider?

RA: Tomb Raider made by Crystal Dynamics was an amazing project to work on. In many ways, I am still saddened I had to leave that crew to join Naughty Dog at the end of production. I remember the pitch I got from the art director at the time that Brian Horton was showing concept art and high level story moments about Tomb Raider in my interview process. I left the interview super excited and got the call back shortly afterwards! The rebooting of such an iconic character “Lara Croft” was something I never imagined in a million years I would be part of. I played Tomb Raider games to death. It was one of the most advanced 3D games of its time! For me, to a be just a small dusting part of this franchise was an amazing honor. I loved working at Crystal and enjoyed the challenges I received as an Environment Artist. I worked mostly on the hub levels of the game which ended up being collectively the levels I am still very proud to have worked on. My prior experience as a level designer helped me in many aspects on this team, and I worked closely with the designers for constructing the spaces before the areas were taken into art. Working with larger teams and everyone having more specific tasks was great! It meant, as an individual, I was able to hone in my skills on the art side vs concentrating on many other aspects. This was perhaps my first project in which I gained the experience of working with a larger team to make a single area. Also, making levels that are so interconnected involved a lot of planning from story to design. On another note: this was also my first company where I dealt with outsourcing and it was a great prep for what was to come at Naughty Dog. Team-wise, what still sticks out to me, is how fondly the “Hub” team talks about each other. The hub team was a full team of Designers, Artists, Scripters, and Coders to make the spaces in the game possible, and, for the length of two years, this team stayed the same almost throughout with only added members. We were the closest friends and, really, it was almost like a team within a team. The hub team was very proud of our work and what we were accomplishing. After seven or so years, we are still very close with each other, and try to occasionally meet up.

GW: You’ve mentioned in the past that your studies at art school provided many different practical and beneficial aspects to your work. For students considering environment art as a career, are there subjects/classes that would be a bonus for them to peruse?

RA: I went to School of Visual Arts in NYC and it was one of the best decisions I made. While I already had “Epic Games” as part of my resume I decided to put a small break on game dev and concentrate on art. I took the time for art school because I felt I needed time to really hone my craft, to the level I wanted to be at. I was already getting a few glimpses to where games might end up. While I was at Epic I was seeing the early development of “Gears of War” which was a game, art-wise, beyond me. If I would have stayed at “Epic Games” I would still likely be a designer, and, in reality, that was not the path I wanted to strive toward. I was already starting to lean toward the art side of game development, so, I knew that that was the benchmark I needed to hit or surpass. The complexity was going to drastically change almost overnight. I decided to give myself time to learn.

One subject that I recommend every aspiring artist to love is history; history is one of the most important aspects, and right after that is Art History which completes the package. I would also look into architecture and graphic design. My first major in school was graphic design and I honestly thought this was going to be a waste of time, but later in my career I found that many principles taught about graphic design apply in game art. I have always been a fan of architecture and for a while I was enthralled with Frank Lloyd Wright's works and many others. As for specific courses, one that is often overlooked or not viewed as important, is color theory. Color theory is one of the most important aspects of creating striking art. Every day in our lives we are manipulated by colors from advertisements to what you wear.

Drawing and sculpting classes are also very important to study forms and structure. The beauty of being a digital artist or an environment artist is that you will have the chance to create worlds that are either based on real life or entirely fantastical. However, without knowing the core foundations first, you will have a hard time to come up with creative designs. I have made it a habit to practice the foundations, and to read and explore them. For a time, I was also really interested in fashion design.

GW: Have you ever encountered “creator’s block” and found yourself stuck? Is there a trick you use to keep yourself going/inspired or a workflow checklist you’ve established?

RA: I know many who suffer from creator’s block and maybe I am lucky to have never really encountered this in my lifetime so far. As silly as it sounds, I live for art. Art is like breathing air for me. If one day I found myself in a situation where I could not be artistically creative, I feel my life would end. I think the main aspect for not having an art block is because I am first an artist before I am a career designated title. I was born an artist and will most likely pass as one. Perhaps one of the reasons I easily find creativity, is that I surround myself with art and have the tools ready to create art at any moment. Since I was a kid, I already loved to draw and had a drawing desk or an area I could freely be creative. I would draw and decorate my walls with drawings of monsters, robots, and anything that came into my mind. Oddly enough, even early on, I did not do much copying. I did not draw ninja turtles exclusively for example; I would create my own designs mostly. I am not really sure how that came to be, but I’m assuming it was just my nature to create my own designs vs copying. But this same drive has continued into my adult age. I try to keep my mind open. Do I have moments of breaks between art sprints? Sure, I do. But, I do not have these large moments of creator’s block, and the reason harkens back to the same reason a professional Olympic athlete can perform under pressure. The endless hours of practice are put to use on daily basis.

Another way to combat creators block is to not be too hard on yourself. Many artists at a later age get trapped into the worst trap of all which is thinking that every single piece of art must be better and better. It is okay to put out work that is not that amazing or just iterate and work on mediocre stuff. The art I release is art that I am comfortable releasing, even if it seems “unfinished.” I have multiple projects or studies that never get finished but it is still general practice and study time. Therefore, my last comment on this is to love art and to not be so hard on yourself; if you enjoy making art you will not struggle doing it.

GW: Your time and energy is so much appreciated, Rogelio! Thank you, thank you, for sharing your experiences and insights!

RA: Thank you, Genese Davis, and thank you to everyone at Gnomon for making me feel like a part of this school in so many ways. I would have loved to study in this school, that is for sure.

Related News

This AAA Game Character Artist Shares her Secrets to Creating 3D Clothing

Mar 25, 2024

Behind the Scenes of David Silberbauer’s Destruction FX Workshop

Feb 07, 2024

An Interview with ZBrush Expert & Gnomon Workshop Instructor Madeleine Scott-Spencer

Sep 22, 2023